Oak Street

ongoing

In 2019 I bought a house. It had gone into foreclosure years before, and sat vacant for almost a decade. It was built at some point in the 1800s, renovated once in the 1950s and again in the ‘70s. When I found it, all the copper in the heating system had been stolen, the roof leaked, the basement was like a jungle, etc. etc. but, as they say, it had good bones.

I ripped out the carpets, wood paneling, a lot of formaldehyde-rich MDF and four drop ceilings. I did all this without a clear plan in mind, but in order to know the house better–removing layers of additions to reach the skeleton, which (I hoped) might show me what it wanted to be.

I ripped out the carpets, wood paneling, a lot of formaldehyde-rich MDF and four drop ceilings. I did all this without a clear plan in mind, but in order to know the house better–removing layers of additions to reach the skeleton, which (I hoped) might show me what it wanted to be.

The house sits on unceded Mohican land (who now go by the Stockbridge Munsee), just about 1000ft uphill from the Mahicannittuk. It faces north, to a paved street, with woods on the south side, which roll into a gulley around a small stream that babbles its way down to the river. When Troy was colonized and industrialized, this part of town was in iron production.

There are half a dozen waterfalls within walking distance to the river, which offered free power for machines. They were measured in horsepower, and were harnessed by 1800s iron-barons to run giant foundries. The majority of horsehoes and railroad spikes in the U.S. were manufactured here. I wonder about the toxicity of the soil, after all that production work. I unearth so much trash no matter where I dig.

There are half a dozen waterfalls within walking distance to the river, which offered free power for machines. They were measured in horsepower, and were harnessed by 1800s iron-barons to run giant foundries. The majority of horsehoes and railroad spikes in the U.S. were manufactured here. I wonder about the toxicity of the soil, after all that production work. I unearth so much trash no matter where I dig.

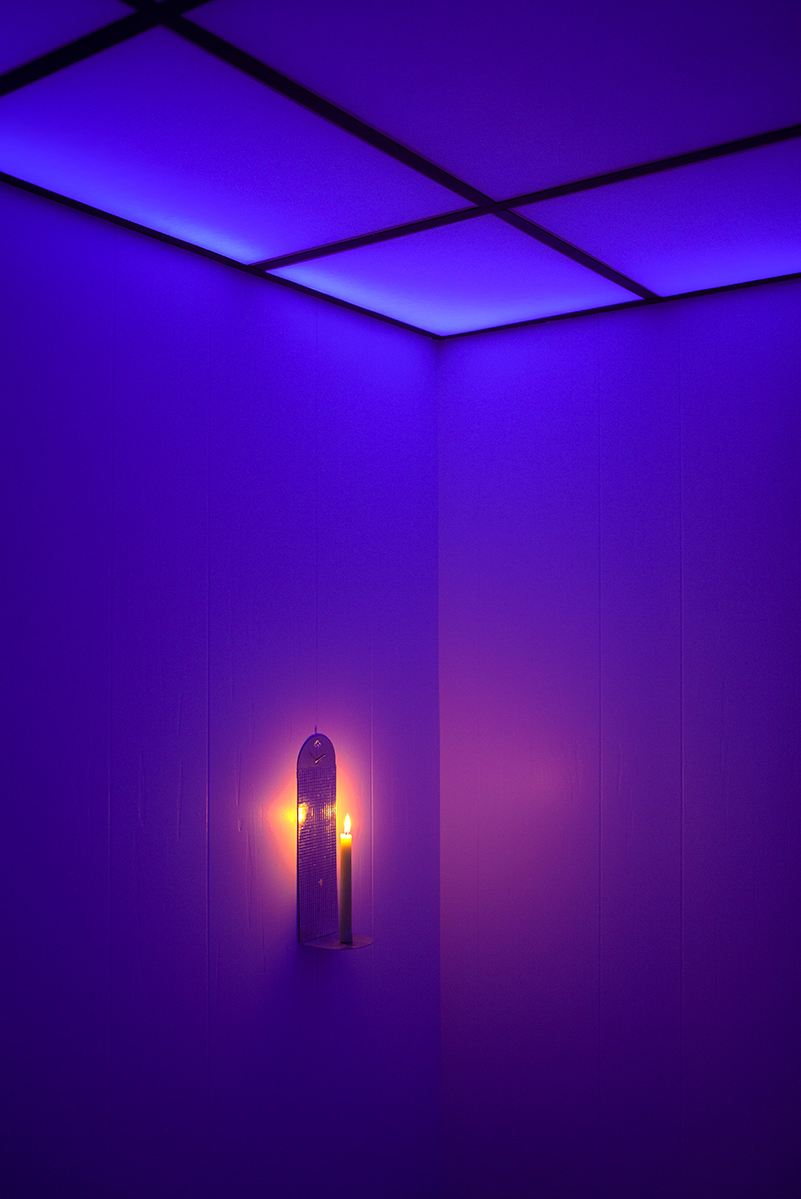

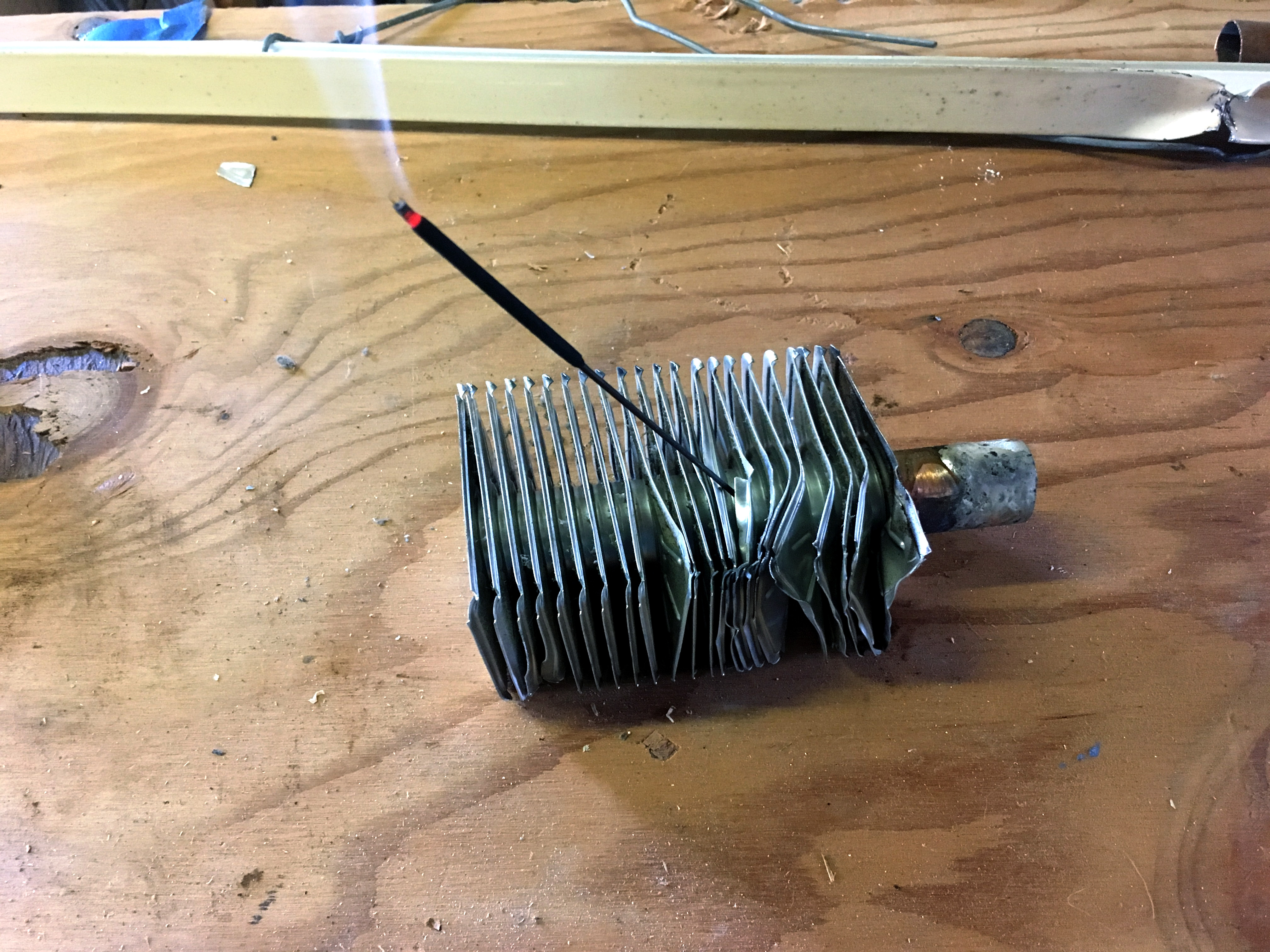

Some of the layers were physical, and some of them olfactory. Freeze-thaw cycles and moisture in the carpets meant that the house stank, somewhere between wet dog and salt&vinegar chips. There were months when I thought it might never go away. To combat the smells, I took to burning incense everywhere I could, using whatever I could find. These quickly became little temporary sculptures: Construction Blessings.

They burned as I worked, the house still stank, I worked more, and after what felt like endless painting, sanding, cutting, removal and open windows and more incense, the smell of mold, cigarette smoke, dog fur, and air fresheners finally retreated (after about 6 months).

I started living here a few months into the project, after one room and the kitchen were clean enough to enjoy, and slowly picked away at it. 2020 was a good year to be engaged at home, and without shows or residencies to go to, it felt good to pour my energy into this structure. It took a long time to get here, but I now see this work as an extension of my sculpture practice (which, in turn, is influenced by years of study and employment in architecture).

Every building has a complex web of stories embedded in it, and I’ve learned a few about this house. Early on, the previous owner dropped by a handful of times to see what it looked like after the sale, and when I gave her a collection of leftover objects and paperwork that was hers, she returned again a week later with some artifacts: a photograph of two residents taken in 1956 and a skeleton key that unlocks the one original door in the house.

It means a lot that she gave me her blessing - she raised her kids here, still lives nearby, and had such a strong connection to the place. She gave me valuable information about the natural springs buried under the house across the street, which yard had the best soil and provided the most veggies, etc. She also left behind half a dozen bird feeders posted up around the yard.

It means a lot that she gave me her blessing - she raised her kids here, still lives nearby, and had such a strong connection to the place. She gave me valuable information about the natural springs buried under the house across the street, which yard had the best soil and provided the most veggies, etc. She also left behind half a dozen bird feeders posted up around the yard.

A house this old has some sag, some tilt, both markers of geologic or structural movement over 150 years, along with the imperceptible presence of those that have died here. This deep time is present here, and the material clues are abundant. Some things are timeless: I would imagine the turkey vultures, hawks and eagles have always used the hill’s thermals to coast and circle above looking for prey.

A house like this, sitting here since the 1870s, bridges the gap between these human time scales and the more eternal ones.

A house like this, sitting here since the 1870s, bridges the gap between these human time scales and the more eternal ones.

Living inside of a project turned out to be more complicated (and hazy) than I had thought. The sheer number of tasks meant that there was a psychic burden attached to whatever I happened to look at. My mind would race through all of the little things that needed to get done and then I’d suddenly realize I’d been standing frozen in a doorway for 5 minutes. That took a long time to get over. I’m not sure exactly what did it, but this is all to say: I went slowly.

I learned traditional plaster along with modern drywall techniques, a bit of plumbing, basic electrical, enhanced my structural understanding and, more than anything else, dirt and dust management. That slow speed ended up becoming a boon to the project, since ideas would emerge naturally; a complicated plan would dissolve immediately when a new, simpler version emerged. Many of the design choices happened this way, and feel strong because of it.

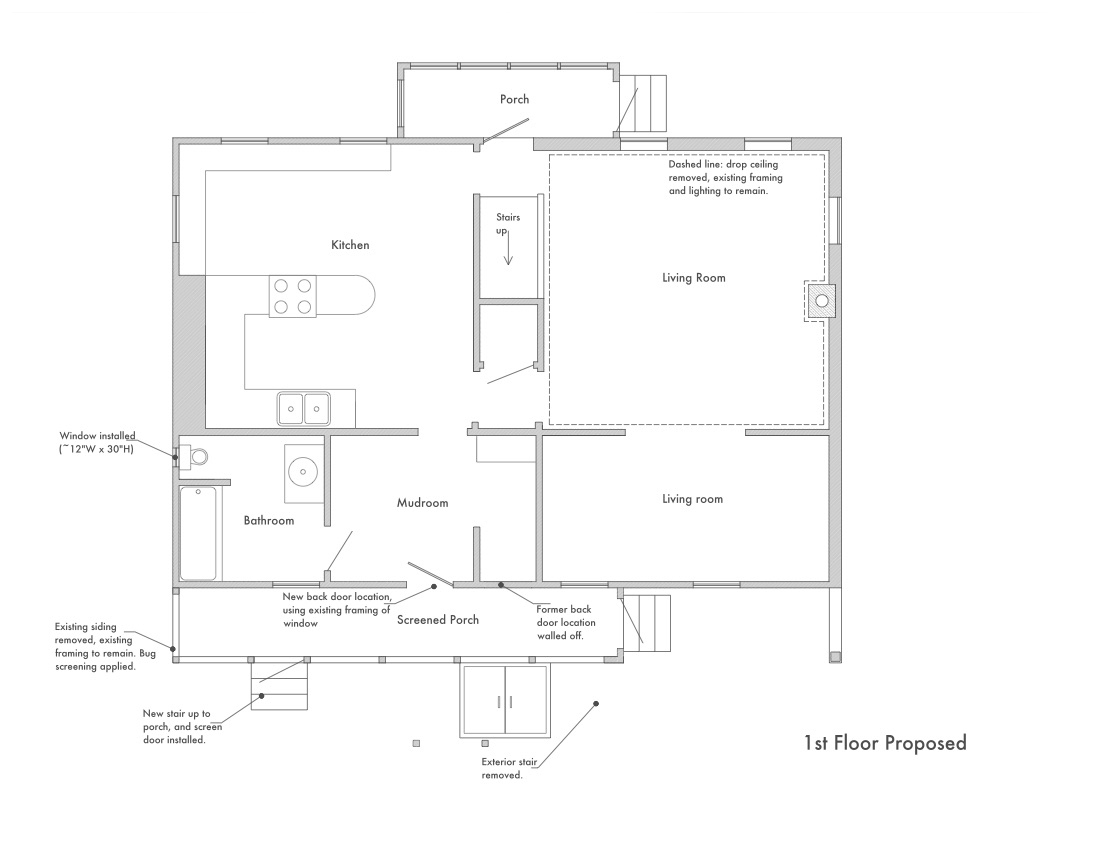

I was working intuitively, and without much of a plan, but once clear ideas for big changes appeared, I needed to go through the code office. The building was techincally still vacant and therefore at risk of massive fines unless inspected, so I drew up plans of the house and applied for permits.

An ethos has emerged along with these ideas: to use and augment what is here before importing any new material. That means taking the low-rent railing and carving a globe into it rather than tossing it into the garbage, cutting a window into the staircase and leaving the original studs exposed rather than spend the energy on a big new header, etc. To avoid getting another dumpster, I made a sculpture out of an old set of exterior stairs:

In the back of the house, I opened up a slim porch that had been added in 1890, and instead of blowing it out, I tried to massage a better flow into it. I moved the back door over ~6 ft, to where a window had been, and added a door to the porch.

With those two small changes, the entry sequence changed dramatically. The backyard is now a straight shot from the kitchen, rather than a long zig zag through a dark hallway. I removed a bit of material, re-used almost all of it, and added a total of four 2x4s, 2 stair stringers, and some paint.

I am far from the first person to champion salvaged materials and cheap renovation, but even that has become monetized as an aesthetic or theme. Actual resourcefulness will never look one way –it always responds directly to the situation at hand.

With those two small changes, the entry sequence changed dramatically. The backyard is now a straight shot from the kitchen, rather than a long zig zag through a dark hallway. I removed a bit of material, re-used almost all of it, and added a total of four 2x4s, 2 stair stringers, and some paint.

I am far from the first person to champion salvaged materials and cheap renovation, but even that has become monetized as an aesthetic or theme. Actual resourcefulness will never look one way –it always responds directly to the situation at hand.

With all of these choices, I’m hoping that the house can begin to speak for itself. Perhaps if I peel away the layered time in this thing, it will start to show the bones of industrialization of this land, and the continued occupation of it. Perhaps I am optimistic (or maybe naive) to think that anything architectural can describe its own toxicity, but I can try. Along with this, I want to make a home that feels good. Perhaps it is too much to ask, but I hope not.

As a culture (I mean “American” construction culture here), we build with too much material. We renovate when we should refine, demolish when we should restore, and build new when we should keep an area wild. We keep building homes. It will be the death of us, and most everyone else; buildings account for the majority of global emissions. Can a different ethos change that?

As a culture (I mean “American” construction culture here), we build with too much material. We renovate when we should refine, demolish when we should restore, and build new when we should keep an area wild. We keep building homes. It will be the death of us, and most everyone else; buildings account for the majority of global emissions. Can a different ethos change that?

In some ways, I’ve approached the renovation as a set of details, and that does seem fitting, since each piece of the house has a very particular flavor to it, described by layers of material from the 1800s, 1950s, ‘70s, ‘90s and the present. There is no sweeping plan, or a pinterest board, but instead an approach. It’s helped me see that the majority of my projects are like that: using a premise (the project) to find a new way to approach the world at large.